Why Your Brain Keeps Chasing That Next Reward: The Science Behind Our Drive for More

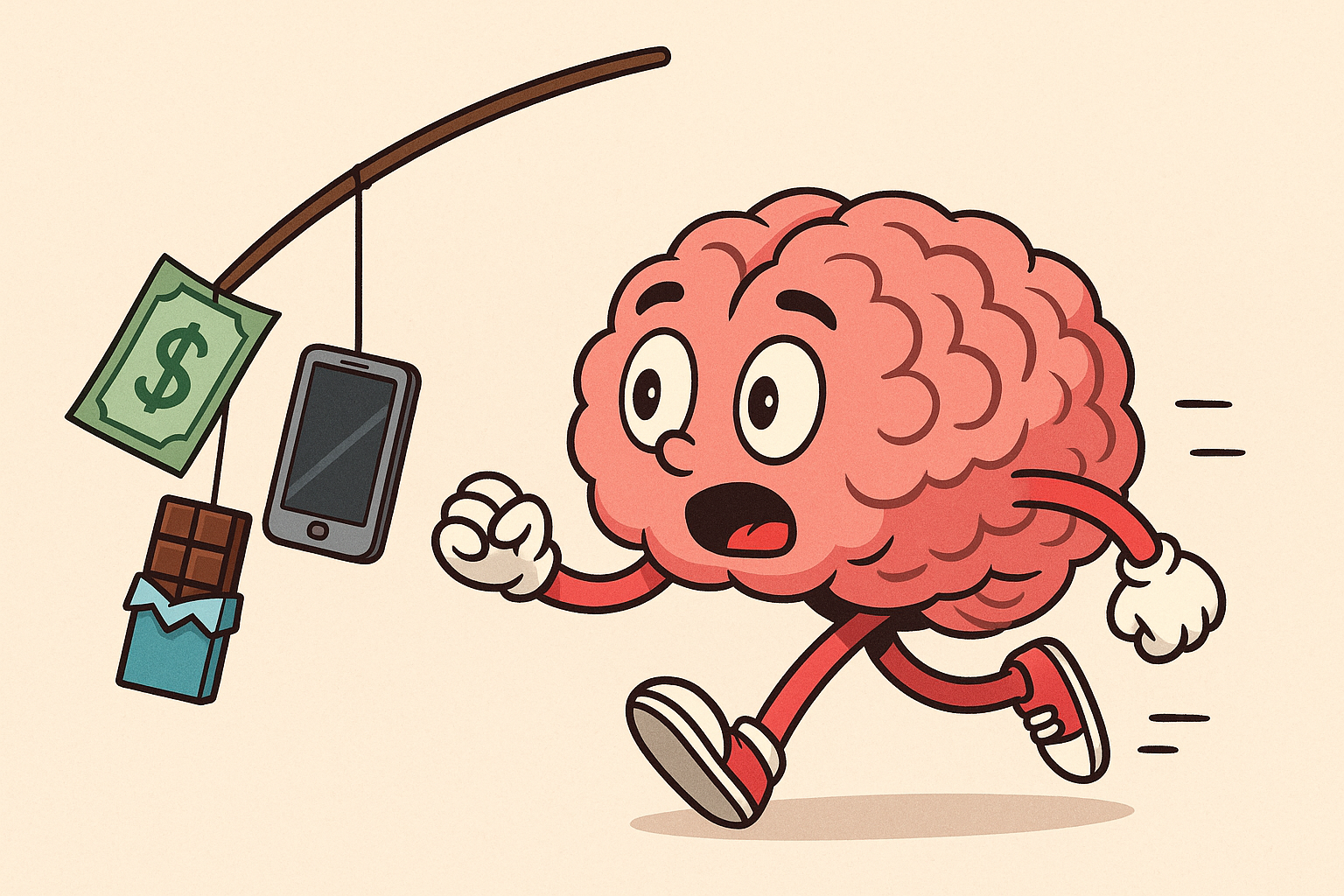

Ever notice how that dopamine hit from checking your phone feels so good in the moment, but leaves you wanting more just minutes later? Or how you can be completely exhausted but still find yourself scrolling through social media at 2 AM? There’s actually fascinating psychology behind why this happens—and it all comes down to how your brain evolved to keep you alive.

Your Brain: The Ultimate Survival Machine

Here’s the thing about rewards: they’re not just nice-to-have experiences. They’re absolutely crucial for survival and reproduction. Your brain basically evolved as a sophisticated reward-seeking machine because organisms that were good at finding food, water, safety, and mates were the ones that survived long enough to pass on their genes.

But how does this ancient survival system actually work in your moment-to-moment experience? Your brain uses rewards in three main ways:

Learning

Rewards teach you what’s important and how to get it. That amazing coffee shop you discovered? Your brain filed that location away as “valuable resource here.”

Motivation

Rewards drive you to seek them out and choose between options. When you’re deciding between Netflix and the gym, your brain is weighing which option feels more rewarding right now.

Positive Emotions

Rewards create those good feelings that make you want to pursue them again. The satisfaction of completing a challenging workout isn’t just nice—it’s your brain’s way of saying “do this again.”

Not All Rewards Are Created Equal

Your brain categorizes rewards into different types, and understanding this helps explain why some things are so much harder to resist than others.

Primary Rewards

The basics: food, water, sleep, sex. These are hardwired to feel good because they directly support survival. You don’t need to learn that water tastes amazing when you’re thirsty—evolution took care of that programming.

Non-primary Rewards

These help you get primary rewards indirectly. Money is the classic example. A twenty-dollar bill doesn’t nourish you directly, but it can buy you food, shelter, or other necessities. Your brain learns to value these tools for survival.

Intrinsic Rewards

These are activities that feel rewarding just for their own sake—exploring, creating music, solving puzzles, reading a great book. These might seem unrelated to survival, but they actually broaden your skills and knowledge in ways that can pay off later. The musician might use their skills to attract a partner, or the explorer might discover new resources.

Interestingly, research shows that computational models incorporating intrinsic motivation actually outperform systems driven only by external rewards in the long run. This suggests that your brain’s tendency to pursue things “just because they’re interesting” isn’t a bug—it’s a feature that makes you more adaptable.

The Prediction Game Your Brain Plays

But here’s where it gets really fascinating: your brain isn’t just reacting to rewards when you get them. It’s constantly trying to predict what’s coming next.

When a stimulus consistently appears before a reward—like your phone buzzing before you see a text message—your brain learns that sound is a reward predictor. Eventually, just hearing that notification sound triggers anticipation and maybe even gets you reaching for your phone.

The key insight here is that simply experiencing things together isn’t enough for strong learning. The reward outcome actually has to depend on the stimulus being there. This is called contingency. If your phone randomly gave you good news whether it buzzed or not, that buzzing sound wouldn’t become such a powerful trigger.

Your brain tracks this through something called prediction error—basically the difference between what you expected and what you actually got. When you get something better than expected, that’s a positive prediction error (surprise and delight!). When you get less than expected, that’s negative (disappointment). When you get exactly what you predicted, there’s no prediction error and no need to update your mental model.

Your Brain’s Teaching Signal

This is where dopamine comes in—and it’s way more sophisticated than just being a “pleasure chemical.” In the context of learning, dopamine neurons specifically signal prediction error. When you get an unexpectedly good reward, they fire in quick bursts. When a predicted reward fails to arrive, their activity drops below baseline. And crucially, when you get exactly what you expected, there’s no change in their firing.

Dopamine isn’t shouting “yay, reward!”—it’s more like “whoa, that was different than I thought!” This surprise signal is what drives learning and keeps your brain’s reward map updated as you navigate the world.

The Complexity of Value

Now here’s where things get really complex: your brain doesn’t just calculate value based on the reward itself. It considers everything—your current internal state, the effort required, how long you have to wait, the risk involved, what you expected based on past experience, and even what’s happening with other people around you.

Think about food. That slice of pizza has completely different subjective value when you’re starving versus when you’ve just finished a huge meal. The same reward, but your brain’s value calculation changes dramatically based on your internal state.

Context matters too. That coffee shop doesn’t just contain coffee—the whole environment has become associated with the good feelings you get there. Your brain literally values the space itself.

And then there’s effort. Your brain clearly calculates effort costs and weighs them against potential payoff. That workout has to feel worth the physical discomfort to be motivating. Interestingly, when you enjoy the activity itself (remember intrinsic rewards?), that intrinsic reward can sometimes outweigh significant effort costs, making hard work feel less burdensome or even pleasurable.

Time also plays a huge role through something called temporal discounting. We almost universally value immediate rewards more than future ones, even when the future reward is objectively better. A reward right now feels better than the same reward next week. This might have evolutionary roots—in an uncertain world, immediate rewards were often safer bets than promises of future payoff.

The Social Element

Your brain is also incredibly sensitive to social factors when calculating value. How rewards are distributed among people definitely matters to your own subjective experience. Getting less than others feels particularly bad (equity aversion), and often this negative feeling is stronger than the positive feeling from getting more than others.

Your brain literally tracks not just your own rewards, but also rewards going to others around you. It even distinguishes who performed the action to get the reward. Your sense of fairness is deeply embedded in your reward system.

When Biology Constrains Choice

This brings us to something profound about free will. All of this sophisticated reward machinery that we’ve been discussing—the prediction learning, subjective value calculation, decision variables—this system that’s so crucial for survival also sets fundamental limits on what we experience as free choice.

Your biological need for essential rewards like food, water, and safety isn’t really a domain of free choice in the philosophical sense. You have to pursue them. When you’re severely thirsty and you choose to seek water, that might feel less like a truly free deliberation and more like following a hardwired intention.

Even when you have multiple options, the underlying drive to maximize utility—to get the most value for survival—imposes significant boundaries on what you’ll seriously consider. Think about habits, or more dramatically, addiction. These are conditions where the very reward system that’s supposed to help you make good choices has been altered in ways that drastically reduce the scope of genuine choice.

What This Means for You

Understanding how your reward system works doesn’t eliminate its influence, but it can help you work with it more effectively. That compulsive phone checking? Your brain has learned that the notification sound predicts social rewards, and it’s doing exactly what it evolved to do—pursue potentially valuable information.

The key insight is that your brain is actively constructing a rich, dynamic landscape of subjective value using sophisticated learning and decision mechanisms that were tuned by millions of years of evolution. Your daily choices—whether to check social media, what to eat, when to exercise—aren’t just arbitrary decisions. They’re the output of an incredibly complex biological system that’s constantly optimizing for what it perceives as valuable for your survival and wellbeing.

This doesn’t mean you’re helpless. But it does suggest that effective behavior change works with your reward system rather than against it. Instead of relying purely on willpower, you can think about how to restructure your environment to change what your brain predicts and values.

The question isn’t whether this biological reward system influences your behavior—it absolutely does. The question is how understanding it might help you make choices that align with your longer-term goals and values, even when your ancient survival brain is pulling you in a different direction.

After all, awareness of the machine doesn’t make you less human. It just gives you better insight into what it means to be human in the first place.