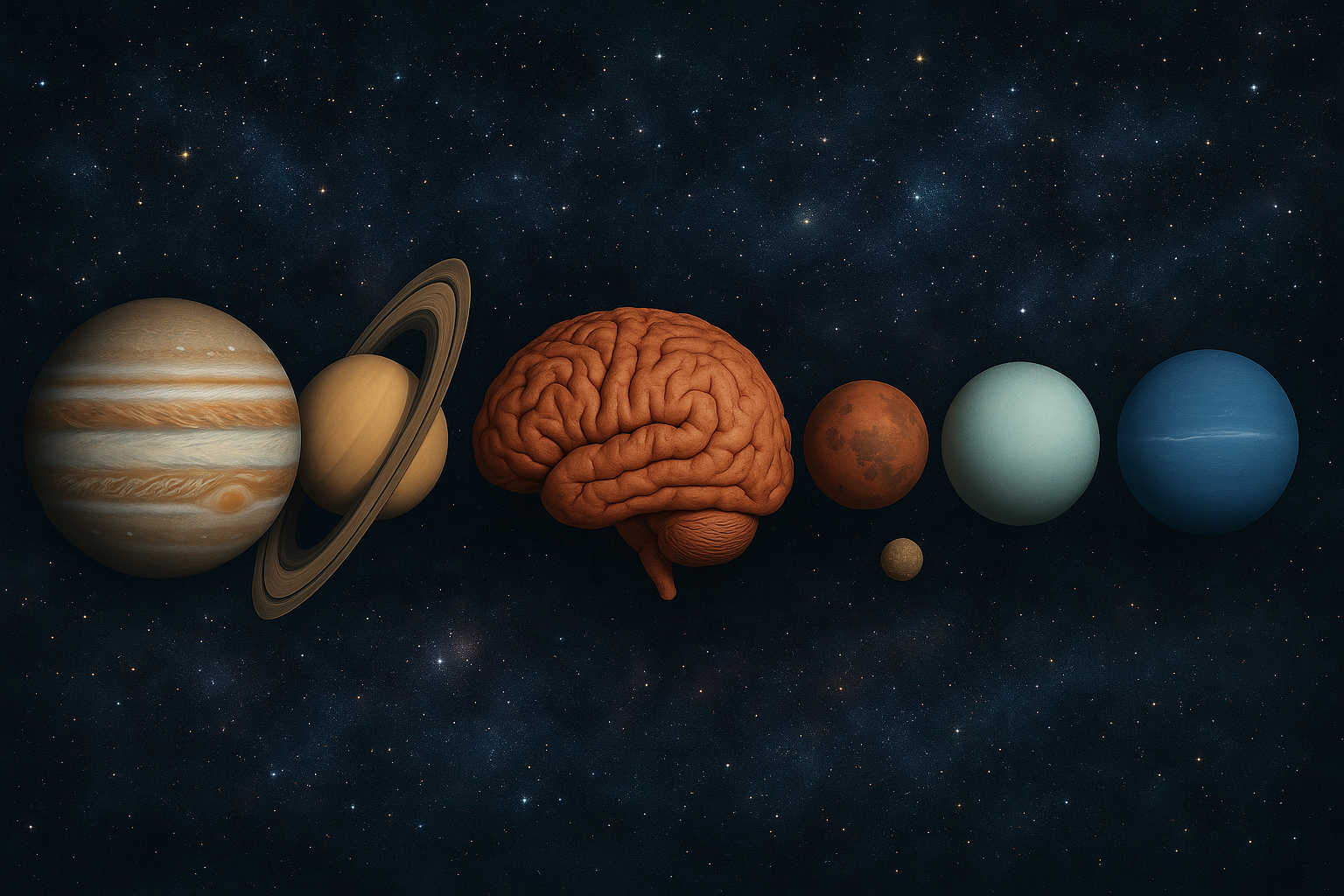

Psychology 101 (Part 1) - Your Mind: The Most Complex Thing in the Universe

Here’s something that’ll blow your mind: according to astronomer Owen Gingerich, while outer space is mind-bogglingly vast, the human brain is actually the most complex physical object we know of in the entire cosmos. Think about that for a second. Forget black holes and distant galaxies—the most intricate thing we’ve discovered is sitting right between your ears.

The Science of Being Human

Psychology isn’t just therapy sessions or common sense dressed up in fancy language. At its core, it’s the science of behavior and mental processes—everything from why you can remember song lyrics from high school but forget where you put your keys, to how we form relationships and make decisions. Psychology as a science (and more recently neuroscience) has spent over a century figuring out how our minds (and brains) work. The complexity is both amazing and, well, a bit problematic. Because our incredibly sophisticated brains have some built-in quirks that can lead us astray.

Sometimes after something happens—let’s say your favorite sports team loses a crucial match—suddenly it feels like you “totally saw it coming”? Or how about when you’re absolutely certain you know something, only to discover you were completely wrong? Yeah, that’s not just you being weird. There’s actually fascinating psychology behind why this happens, and understanding it might just change how you look at the world.

What makes psychology particularly fascinating is how it challenges our intuitions. You know those contradictory sayings we all love? “Absence makes the heart grow fonder” versus “Out of sight, out of mind.” They can’t both be universally true, right? This is where scientific thinking comes in—rather than just accepting what feels right, psychology demands evidence.

Three Mental Traps We All Fall Into

The research reveals three major ways our brains consistently “trick” us, and honestly, once you know about them, you’ll start seeing them everywhere.

1. The “I Knew It All Along” Effect

Picture this: you’re watching the news about some major political event or economic shift, and as the story unfolds, you think, “Well, of course that happened. It was so obvious.” This is hindsight bias, and it’s incredibly powerful.

Here’s the thing—when researchers tell people about an outcome and ask them to explain why it makes sense, they can do so brilliantly. But show them the same information beforehand and ask them to predict what will happen? Suddenly it’s not so obvious anymore.

This bias makes us think we’re much better at predicting the future than we actually are. It’s like having a superpower that only works backwards. The problem is, this overconfidence in our predictive abilities can lead us to make poor decisions going forward.

2. The Confidence Trap

We’re consistently more confident than we are correct. Think about those word puzzles where you rearrange letters—like turning “OCHSA” into “CHAOS.” Once you know the answer, it feels like you would have gotten it immediately. But hand someone a new puzzle they haven’t seen before, and suddenly it takes much longer.

This overconfidence isn’t limited to word games. Research by Philip Tetlock showed that experts making confident predictions about world events were wrong more often than right. History is littered with hilariously overconfident predictions—like Wilbur Wright saying humans wouldn’t fly for a thousand years (in 1901, just before his brother proved him spectacularly wrong).

3. Seeing Patterns in Randomness

Our brains are pattern-detection machines, which is usually helpful. But sometimes we see meaningful patterns where none exist. We spot faces in clouds, think basketball players have “hot hands” when it’s just random variation, or believe we’ve cracked some cosmic code when we win the lottery twice.

The reality? Random sequences often don’t look random to us. With a large enough sample size, seemingly impossible coincidences become statistically inevitable. If something has a one-in-a-billion chance of happening to any person on any given day, it’ll still happen to about seven people worldwide every single day.

Why This Matters in Our “Post-Truth” World

These mental quirks make us vulnerable to misinformation. Consider this: many Americans believe crime rates are rising when they’ve actually fallen dramatically over decades. Or think about how anecdotes about vaccine side effects feel more compelling than comprehensive data showing dramatically lower death rates among vaccinated populations.

We fall for this stuff because of confirmation bias (seeking information that confirms what we already believe), emotional reasoning (if it feels true, it must be true), and simple repetition (hearing something multiple times makes it feel familiar and therefore credible).

Fighting Back with Scientific Thinking

So how do we combat these built-in biases? The answer lies in adopting what psychologists call a “scientific attitude”—a combination of curiosity, skepticism, and humility.

Curiosity means staying genuinely interested in understanding how things really work, not just confirming what you already think.

Skepticism doesn’t mean being cynical about everything, but rather demanding evidence. Remember James Randi, a Canadian-American stage magician, author, and scientific skeptic who extensively challenged paranormal and pseudoscientific claims, tested someone who claimed they could see auras? His simple challenge: “Can you see my aura if I stand behind this wall?” When they refused the test, that told the whole story.

Humility might be the most important piece. It’s acknowledging that we all make mistakes and being willing to change our minds when evidence points in a different direction. As they say in psychology labs: “The rat is always right”—if your hypothesis doesn’t match the data, your idea might be wrong.

Putting This Into Practice

Here’s what you can do with this knowledge:

Slow down your thinking.

When you feel certain about something, especially if it confirms what you already believe, pause and ask: “What evidence am I basing this on? Could I be wrong?”

Seek out disconfirming evidence.

Actively look for information that challenges your views. It’s uncomfortable, but it’s how you grow.

Remember the Royal Society motto: “Take nobody’s word for it.”

Test ideas when you can, and be willing to live with uncertainty when you can’t.

The goal isn’t to become paralyzed by doubt—it’s to become more accurate in your thinking. Understanding these mental quirks doesn’t make you immune to them (I still fall for them all the time), but it does give you a fighting chance.

Your brain is indeed the most complex thing in the known universe. The least we can do is try to understand how it works—and where it might be leading us astray. Because once you start thinking like a scientist about your own thinking (so meta), you’ll never look at the world quite the same way again.

What’s one belief you hold strongly that you’ve never really questioned? What would it take to change your mind about it?